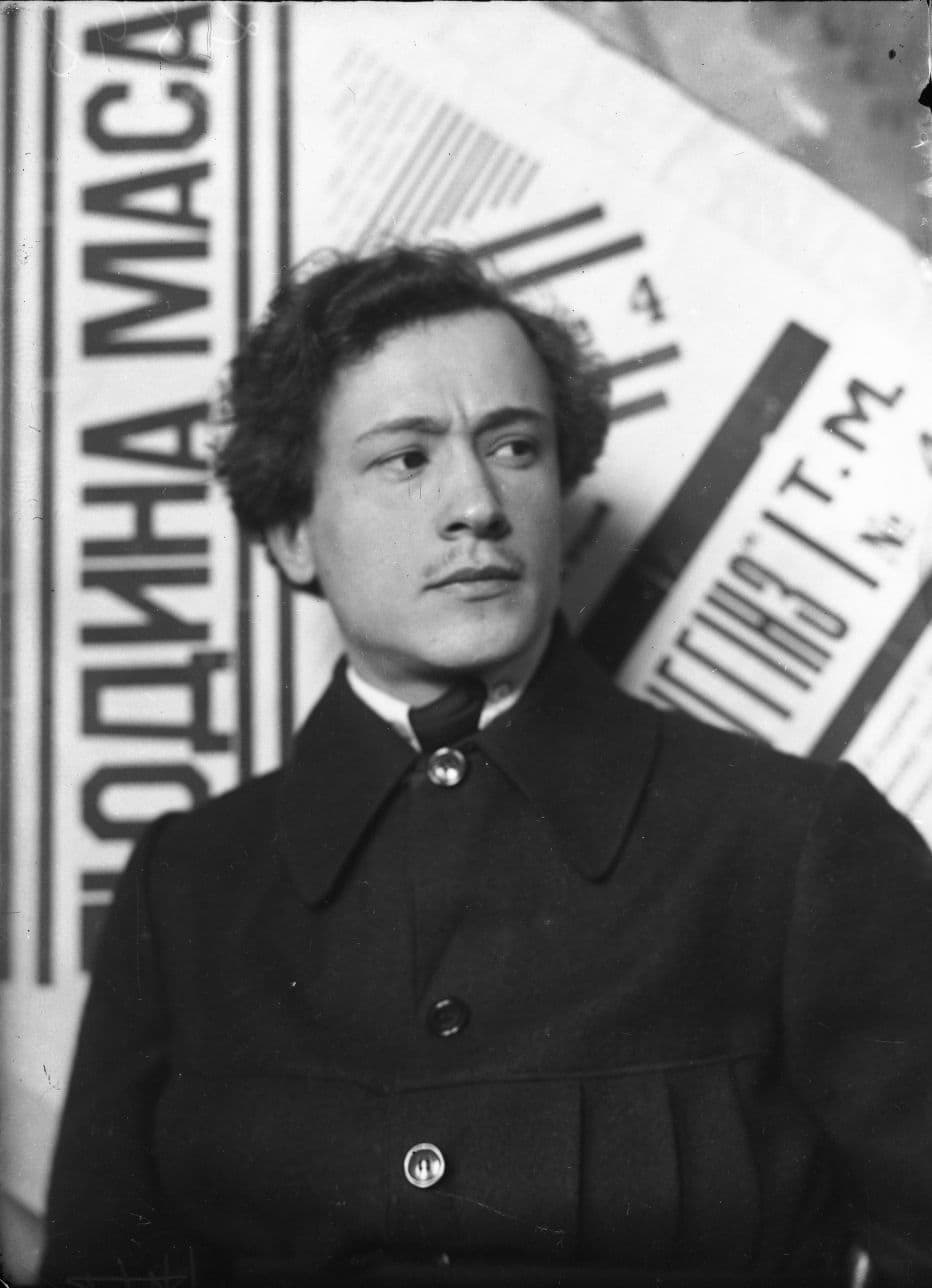

The Berezil Artistic Association was established in Kyiv on March 30, 1922 by Les Kurbas. Kurbas borrowed the association’s name and credo from Norwegian poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s poem “I Choose March,” and Berezil was seen as the concentration and realization of all the most advanced creative intentions of Ukrainian theater at the time. Berezil creative staff included actors representing different generations and levels of experience (A. Buchma, Y. Hirniak, M. Krushelnytskyi, I. Marianenko, R. Neshchadymenko, V. Chystiakova, and others), artists, writers, musicians, other artistic professionals. It’s no surprise that N. Yermakova called it “the cornerstone in the foundation of a new stage culture.”

Berezil’s four years can be divided into several stages: 1. Laboratory; 2. Revolutionary propaganda; 3. Repertoire.

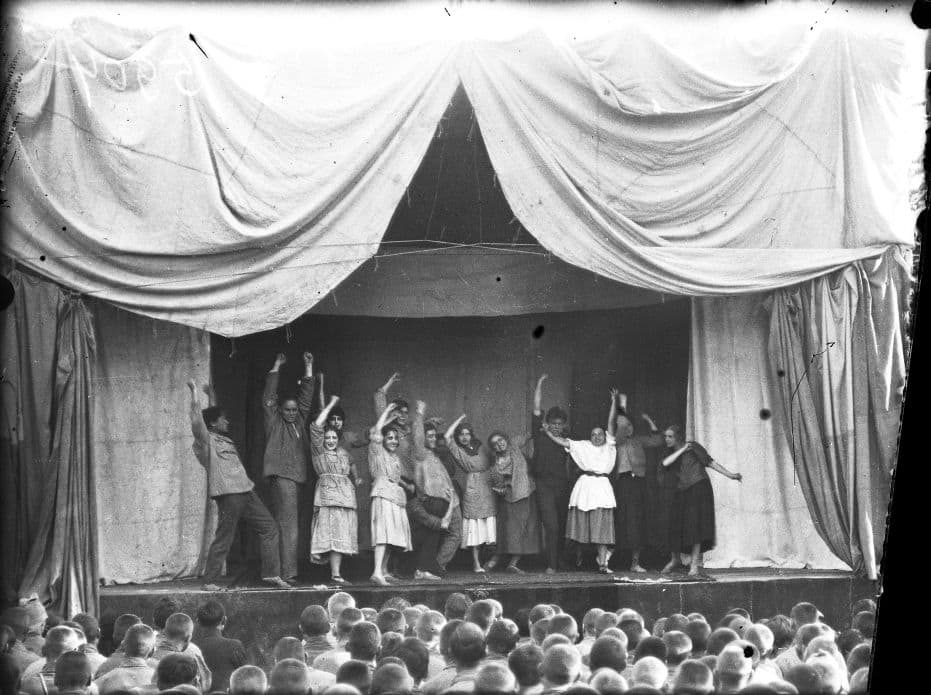

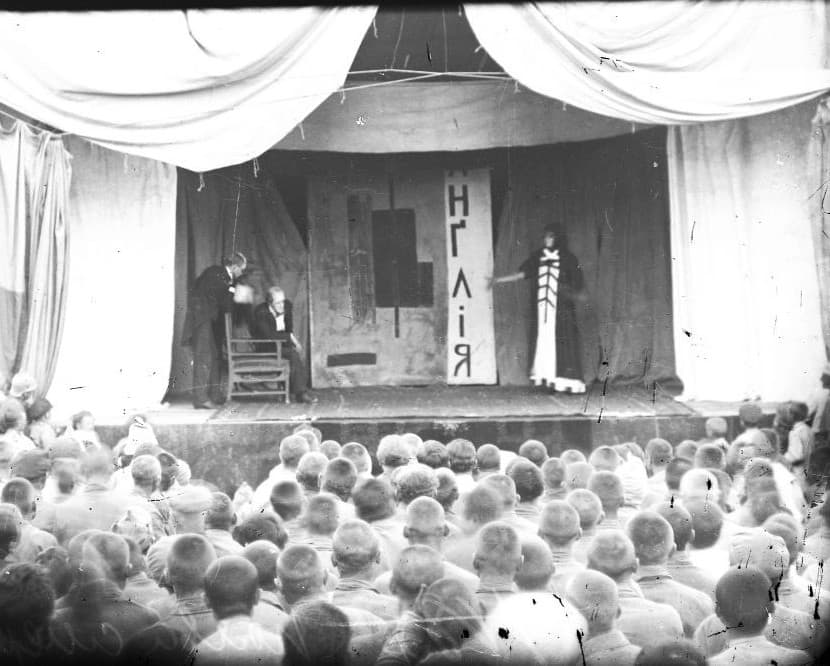

The first stage, during which the performative pantomime performances October (November 11, 1922) and Ruhr (February 24, 1923) were brought to life, consisted predominantly of studio classes and trainings.

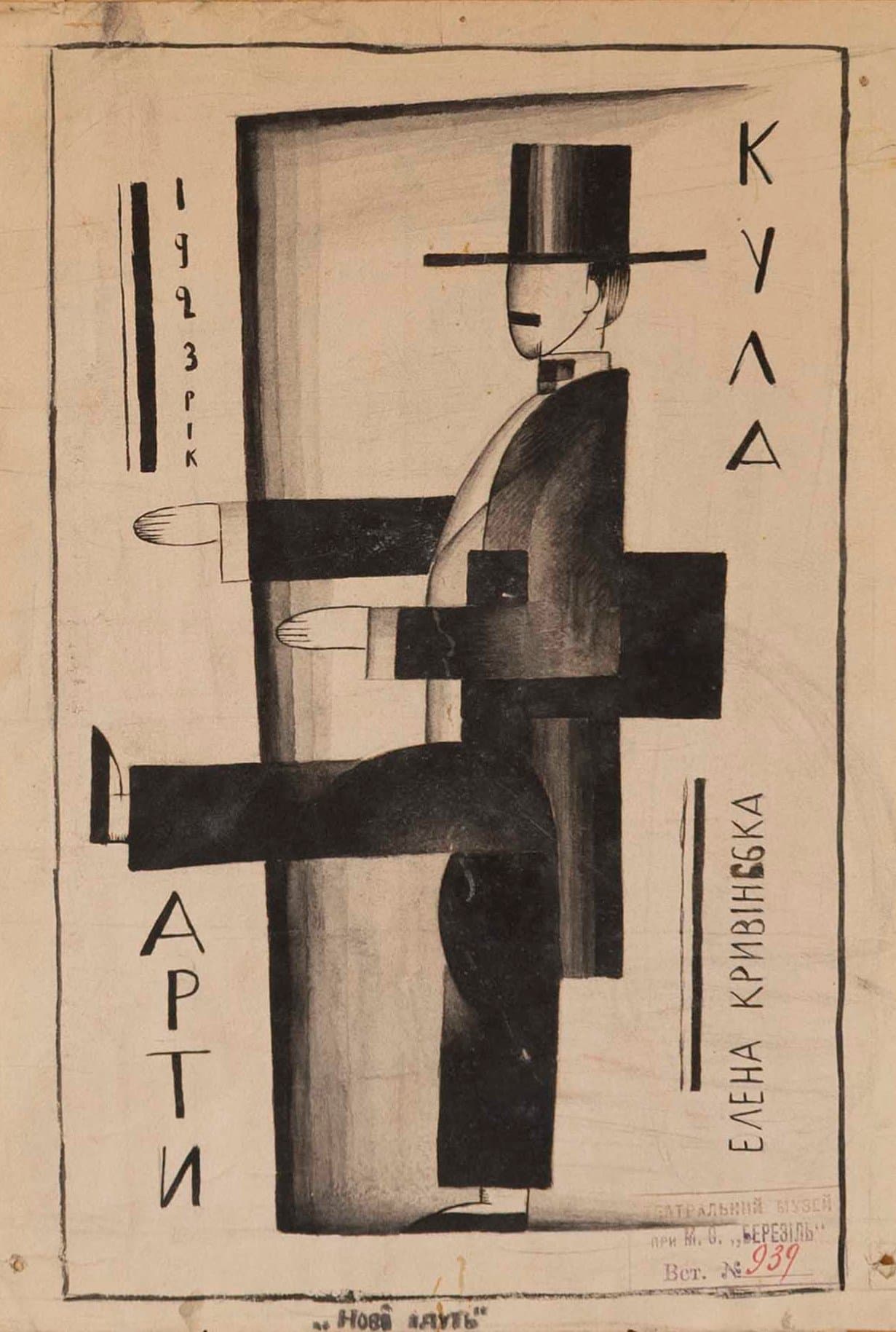

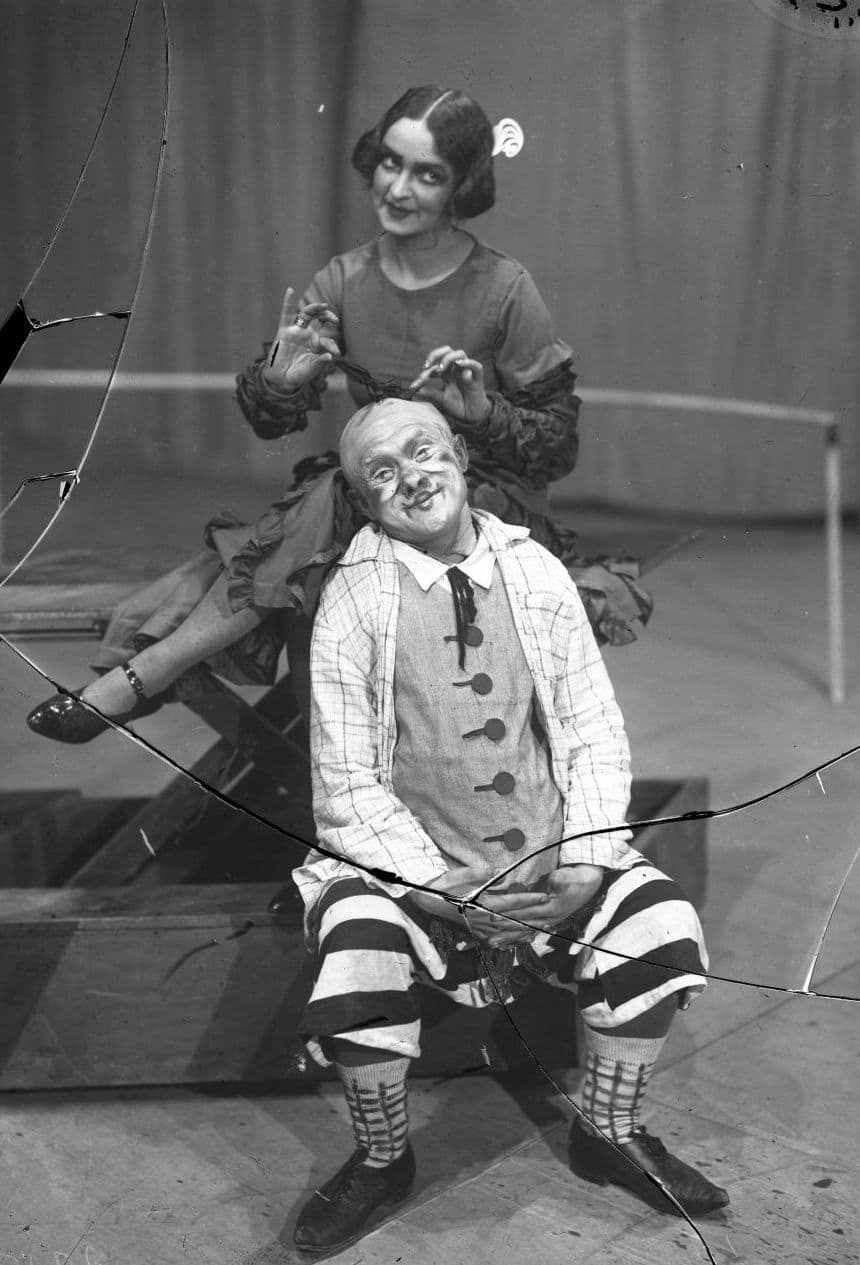

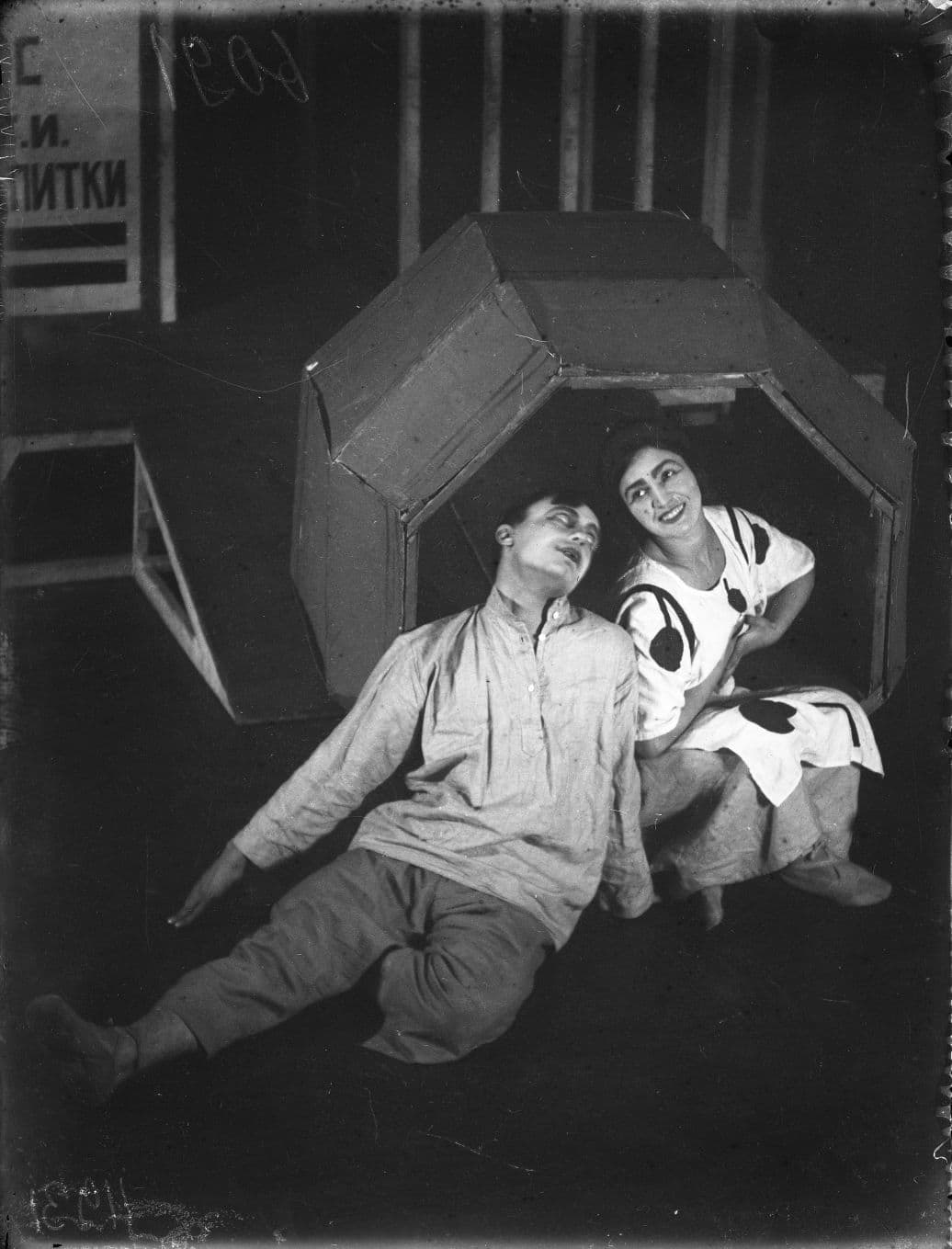

The second stage, which began with the production of Georg Kaiser’s Gas (April 27, 1923), was marked by the introduction of the figurative language of the avant-garde: expressionism and constructivism. Les Kurbas’s subsequent productions – Upton Sinclair’s Jimmie Higgins (1923) and Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1924) – were also esthetically innovative. His students performed with the same experimental spirit: F. Lopatynskyi’s adaptations of Efim Zozulya’s The New Ones Advance, Ernst Toller’s The Machine Wreckers, and M. Kropyvnytskyi’s They Made Fools of Themselves; H. Ihnatovych’s adaption of Ernst Toller’s Masse-Mensch; B. Tiahno’s adaptation of Leroy Scott’s The Walking Delegate.

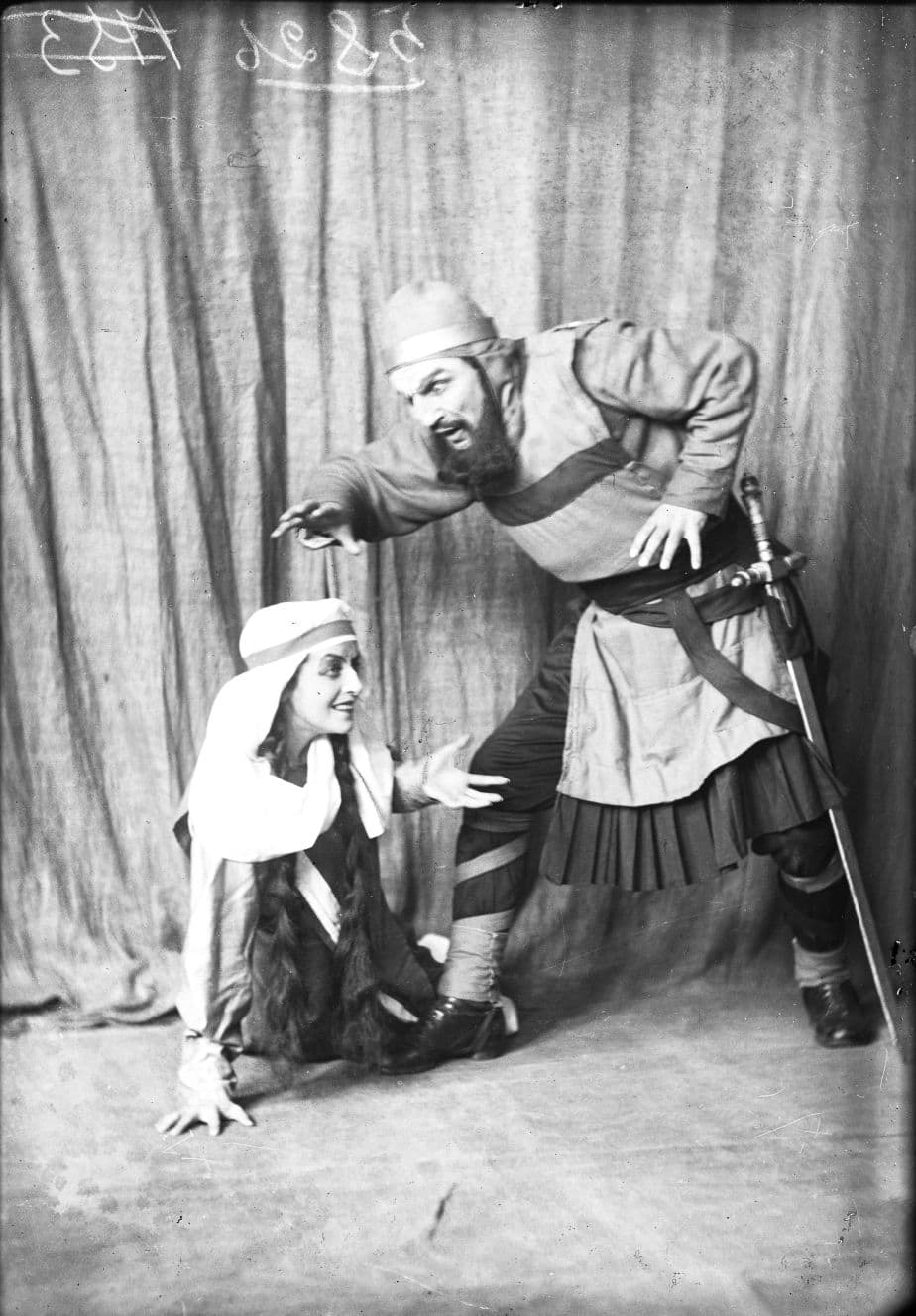

The third stage was marked by a focus on repertoire theater, which manifested itself in P. Bereza-Kudrytskyi’s staging of M. Kulish’s Commune in the Steppe; B. Tiahno’s staging of P. Mérimée’s La Jacquerie; V. Vasylko’s staging of M. Starytskyi’s Chasing Two Hares; and Y. Bortnyk’s staging of V. Yaroshenko’s Riff-Raff.

During its first two years, Berezil engaged in studio work and performed at various venues in Kyiv, mostly at the Taras Shevchenko Theater (formerly the Bourgogne Theatre, today the Lesia Ukrainka National Theater of Russian Drama). The 1924-25 season opened on November 7, 1924 at the Vladimir Lenin Theater (formerly the Solovtsov Theater, today the Ivan Franko National Theater), where Berezil performed before moving to Kharkiv in June 1926. Berezil actors went on several tours to Kharkiv, Poltava and Odesa.

Berezil had a complex structure where each of the departments – stations, committees (museum, psycho-technical), labs (sound, photo), branches – performed clearly defined tasks and functions. There were several acting workshops (First, Second and Fourth in Kyiv, Third, Fifth and Sixth not in Kyiv) and branches (Odesa) that spread Berezil’s experience throughout Ukraine.

Berezil had a director’s lab (later director’s staff) which laid the foundations of a new school of directing in Ukraine. A set design school was established in the modeling workshop under the leadership of V. Meller (students included M. Symashkevych, V. Shkliaiv, D. Vlasiuk, E. Tovbin, and others). A body of new Ukrainian plays was created in the drama workshop, some of which were performed in Ukrainian theaters. The choreography workshop led by N. Shuvarska trained a new kind of plastic actor.

Improving technique through classes in acting and movement was one of the key aspects of Berezil. By cultivating “stage practice,” Les Kurbas formed the Berezil acting school, where the concept of “transformation” became fundamental.

Berezil’s creative activities were accompanied by the applied, theoretical and journalistic activities of Kurbas and his students: they conducted sociological research in the theatrical sphere, published the journal Theater Barricades. Members of Berezil regularly published articles about their artistic experience.

But the public reaction to Berezil’s artistic achievements was mixed: members of the old national intelligentsia, including S. Yefremov, didn’t approve of Les Kurbas’s experiments. Part of the reason was that Berezil’s work was no stranger to the Soviet government’s political slogans (for example, Les Kurbas’s On the Eve) and it was personally supported by the influential military figure Iona Yakir.

Berezil’s move to Kharkiv made its reorganization into a regular repertory theater inevitable. But, as N. Kuzyakina noted: “The move was supposed to solve Berezil’s many problems in one fell swoop: help achieve financial stability through the subsidy given theaters in the capital and to create a good environment for the audience.”