Les Kurbas

Лесь Курбас. 1910-ті

Родина Леся Курбаса. Батько – Степан Янович, мати – Ванда Яновичева, сестра Надійка. 1910-ті

Лесь Курбас і Валентина Чистякова - весільне фото. Київ,1919

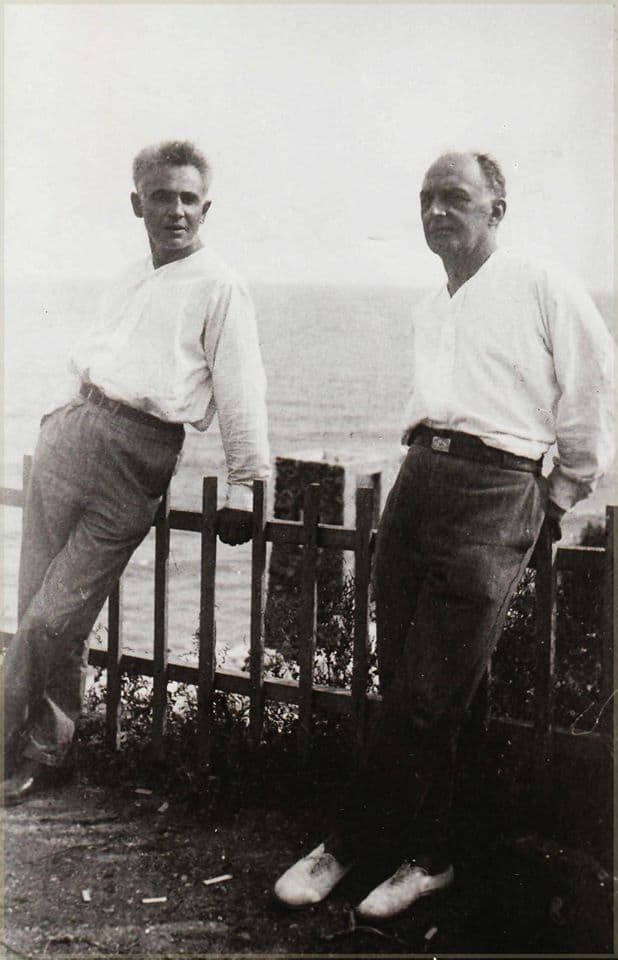

Лесь Курбас і Вадим Меллер. Одеса, 1927

Les Kurbas – the outstanding 20th century Ukrainian artist, actor, theater and film director, theater theorist and organizer, publicist, translator and playwright – was a uniquely multifaced individual. Much remains unknown and misunderstood about this legendary figure’s life, family, circle of friends, aesthetic and political views, and creative achievements. The very fact that for a long time many publications listed an erroneous place of birth and death conveys the degree to which the artist has been mythologized from the hundreds of stories about him.

The Open Kurbas project, through the digitalization of museum archives and online access to the vast collection of documentary evidence, provides the foundation for a biography that sheds light on the artist’s diversity and his influence on Ukrainian society. Open Kurbas is an important resource for foreign studies about Kurbas and popularization of his work (which remains largely unknown to the general public) that aims to preserve and honor the memory of this great director.

The Beginning

Les (Oleksandr-Zenon) Kurbas was born on February 25, 1887 to actors Stepan Kurbas and Vanda Teicher (stage name Yanovych). It took researchers more than a decade to establish his exact place of birth: Sambir, the location of the Galician acting troupe the future director’s parents belonged to. From the memoirs of Kurbas’s childhood friend Khoma Vodianyi and a published photo of the church record of his baptism in Przemyśl in January 1888 we learn that his grandparents were Father Pylyp Kurbas and Yosypa (Osypa) Lytvynovych from Staryi Skalat.

The years that Kurbas spent as a child and adolescent in his grandfather’s home in the Ternopil region and traveling with his parents’ acting troupe is one of the darkest shades of his life. The artist didn’t talk about them, nor did his mother Vanda Teicher, who spent her last years living in Kharkiv with her daughter-in-law, actress Valentyna Chystiakova. The routine of traveling theater was one of the causes of Kurbas’s father’s mental illness, an issue the family preferred not to discuss.

Pylyp Kurbas – who separated his son from their family because he didn’t finish high school, started acting, and married an actress at a young age – had a very negative opinion of the theater. In the Kurbas-Yanovych family the parents were artists, both grandmothers were involved in acting, but everyone was against the gifted son and grandson following the same exhausting and thankless path.

Les’s mother’s relatives paid for his university studies in Vienna under the condition that he would not go into theater. So, after graduating from the Ternopil gymnasium Kurbas went to the capital of the empire to get a “normal” profession that would allow him to support himself and his family. But his mother’s restless premonition that her son was doomed to join the theater came true. Les became an actor and director against his family’s will.

After his father’s death in 1908, Kurbas is forced to return home and continue his studies at Lviv University. Under the influence of his uncle Roman, the young Kurbas becomes fascinated with leftist ideas and the desire for national self-affirmation and self-realization. The desire to radically reform Ukrainian theater became a revolutionary political current. For the young man the theater became an outlet for important personal statements and missionary messages – because it was an art. Kurbas was able to speak more convincingly to the world through the language of art, influence and expression.

Lviv

Kurbas began his theatrical career in Lviv. He made his directorial debut – Yevhen Chyrykov’s sensational play Jews about the pogroms of the 1900s – with an amateur student group in 1909, and received a laurel wreath for his role as Nachman. One of the members of the student group was the rebellious Adam Kotsko, who was later killed in a political skirmish in the hallways of the university. His close friendship with Kotsko cost Kurbas: the Austrian authorities were unforgiving of untrustworthy, free-thinking Ukrainian students and in 1910 he was expelled from the university.

It is then that Kurbas’s circle of contacts expands to include artists Volodymyr Vynnychenko and Hnat Khotkevych – political emigrants from Greater Ukraine. Their work played a decisive role in this stage of the young man’s life. In 1911 he became the administrator and co-director of the Hutsul Theater founded by Khotkevych, and in 1914, already a professional actor at the Ruska Besida Theater, he played one of his most notable roles – Korniy in Vynnychenko’s Black Panther and White Bear.

Kurbas founded his first theater – Ternopil Theatrical Evenings – together with friends in 1915 as a way to help actors who found themselves between the fronts of WWII in Russian-occupied land survive and feed themselves. The theater operated in the frontline zone and most of its spectators were Ukrainian soldiers in the tsarist army. They performed the usual ethnographic repertoire led by Natalka Poltavka, Ukrainian classics, as well as modern plays by Vynnychenko. For Kurbas this was most likely a conscious attempt to germinate the Ukrainian spirit in a gray indoctrinated mass that was starting to remember their upbringing and become self-aware.

In 1916, having crossed the border between two hostile empires (Austro-Hungary and Russia) that was marked by the narrow Zbruch river, Kurbas would never again return to his native land. More so, he dragged his Galician friends and acquaintances – Yanuarii Bortnyk, Amvrosii Buchma, Yosyp Hirniak, Volodymyr Kalyn, Marian Krushelnytskyi and Favst Lopatynskyi – over to Greater Ukraine.

Kyiv

In March 1916 Kurbas makes his premiere with the Mykola Sadovskyi Theater in Kyiv. He organizes an actors’ studio at the Young Theater and a little over a year later the Young Theater opens with a repertoire that is new and unusual for the Ukrainian stage. Many saw this as a fool’s errand, but it was this “society of faith” that went down in history as the first modern Ukrainian theater.

The Young Theater started out with no financial support – just the generous permission by entrepreneurs to sometimes perform for free at the Bourgogne Theatre on Fundukleivska Street. Everything that was brought from home, borrowed from neighbors and others and made possible through the enthusiasm and voluntary participation of people full of hope and expectations, built a theatrical frame that was cemented by the performers into an aesthetic whole. They were creating art of a new quality in an unfamiliar way for most: a young actors’ studio, updated repertoire and principle of non-commercialism.

The Young Theater years were the most prolific time of creative apprenticeship for Les Kurbas, Hnat Yura, Pavlo Tychyna, Mykhailo Semenko, Anatol Petrytskyi, and many others. It is then that Kurbas realizes that theater is a way to deliver personal statements, missionary messages and social manifesto. In 1920 he stages the allegorical play Haidamaky, which would become one of the most significant milestones in 20th century Ukrainian theater.

In a photo from the early 1920s Kurbas looks excited, inspired and full of energy. His idealism (belief in a better future) and maximalism (focusing all his efforts for an important cause) inspired him to create a revolutionary propagandist theater. Founded in 1920, the Kyiv Drama Theater (Kyidramte) followed the Bolshevik detachments and essentially became part of Iona Yakir’s Red Army Division. “There were those who cried. There were those who became conscious Ukrainians only because of our performances,” the director wrote after a performance for Red Army soldiers in Uman on August 31, 1920.

In 1922 Kurbas is back in Kyiv. Surrounded by new friends and like-minded people, he organizes the famous Berezil Artistic Association. Berezil staged expressionist plays full of sadness, despair and premonitions of industrial collapse in a relaxed avant-garde style, as a kind of ode to liberated labor. Those who saw Georg Kaiser’s Gas were impressed by the intense scenes where dozens of actors moved like a single giant creature. Berezil’s metaphorically persuasive, allusively ambiguous, technically complex and semantically full show was the beginning of what would grow to become a full-blooded artistic whole – Kurbas’s phenomenal theater.

Kharkiv

Starting in autumn 1926, Berezil – the most respected Ukrainian theater of the time – is located in the then capital of Kharkiv. Kurbas draws intellectuals, aesthetes and leftwing radicals to his theater and creates a powerful artistic environment. But the audience doesn’t always appreciate his work. The Kharkiv audience unwillingly swallowed Fernand Crommelynck’s Golden Guts about greedy, imbecilic burghers. People couldn’t understand the irony and caricature of whimsical human temperament. The audience and critics alike were curious as to what would happen to the theater after it had outgrown its revolutionary period and aspired to intellectually critical performances.

Berezil’s program for the late 1920s combined two realities. In 1927 they revived the most successful show from their Kyiv period: Upton Sinclair’s Jimmie Higgins, about the revolutionization of the American proletariat. They revived the play about the Russian Revolution that came to be known as Prologue. On the anniversary of the revolution they staged the publicist propaganda piece October Review. In 1928, Malakhii Stakanchyk from Mykola Kulish’s play starts wandering the Kharkiv streets, recreated on the Berezil stage by artist Vadym Meller, with clarity and ease.

Soviet life In The People’s Malakhii doubled and split into unequal parts: people ran through the streets bewildered from hunger while Malakhii’s daughter Liubunia went to a brothel and Stalin’s falcons rode in cars and swooped down. Presenting industrialization on stage – with its frantic pace of pouring concrete and card system for food alongside the operettic luxury of the Soviet bureaucracy – was dangerous.

Kurbas clearly felt incompatible with Kharkiv and its new well-fed partocracy. In the comedy Myna Mazailo in 1929 he seemed to portray himself – a former dreamer inspired by future revolutionary changes. Mokii, a boy who is always reading books, flipping through dictionaries and learning languages, is immersed in his bookish obstinance just like Kurbas – an intellectual immersed in books, secluded and detached from everyday life, who swallowed piles of literature written in at least five languages.

Everyone who visited him (he lived on the fifth floor of the Slovo House writers’ building) couldn’t help but notice his ascetism: shelves full of books covered the walls from floor to ceiling, newspapers and magazines were strewn everywhere. According to those who knew Kurbas well, he had no interest in fun for fun’s sake: the director’s favorite pastime was going for a walk or hiking. The only game he played beyond the stage was Sixty-Six – a card game his mother Vanda Adolfivna liked.

In the late 1920s Kurbas stages a repertoire coup in Berezil. He puts on the operetta The Mikado, the collective performance-revue Hello, This is Radio 477, and initiates the organization of a new Ukrainian operetta theater. The director offers what seems like entertaining theater but is actually critical and ironic theater where everything is built on satire and mockery, where the actresses’ legs are a joy to see, while the show’s authors deride the bourgeoisie. But the Marxist-Leninist critics caught on to his “deception” and became increasingly harsh and repressive towards Kurbas’s directorial and theatrical inventions.

The critics exposed the opera Dictatorship for its mystery of form (small birdhouses for each character) and essence. They saw that this show, where the text was sung rather than spoken and the chopped words of Mykytenko’s play were recited, wasn’t at all about the “apostolic” movement of the Twenty-five-thousanders, but about the destruction of the Ukrainian peasantry through forced collectivization. Berezil couldn’t even be saved by the fact that from time to time giant factories were erected on the stage and the actors, like in Dictatorship (1930), moved by means of a crane.

Kurbas fully realized his “theater of manifestation,” which he wrote about back in 1925, in Berezil’s last show, Maklena Grasa, about a poor girl from bourgeois Poland. After this production, which was performed in September 1933 as a universal lament, the authorities would no longer risk trusting the theatrical helm to the unreliable utopian dreamer.

The End

According to the transcript from October 5, 1933, Kurbas was removed as head of the theater he founded for Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism. All but two people present voted against the “fascist-nationalist.” The group then asked the authorities to rename Berezil the Taras Shevchenko Theater. Some tried to eliminate all mention of Kurbas and erase him from the individual and collective memory. The son of the director’s close neighbors at Slovo House, who used to listen to the adult conversations as a child, wrote in his memoirs: “Kurbas’s students and colleagues also accused him of being a Petliurite, a saboteur, and an antisocial pipe dreamer.”

Kurbas wasn’t forgiven for his creative enthusiasm, perseverance, or sincere belief in what almost none of the pragmatists no longer believed in. After all, this was a chain reaction by ordinary people, because his demands, harshness, intolerance of the everyday, chatter, mummery, “sitting under the pear tree” increasingly annoyed envious opponents.

Whether inherited from his actor parents or priest grandfather or ingrained from his opposition to the everyday, his disappointment from life and sadness over unfulfilled dreams, his overwhelming belief in art’s missionary capacity led him to be creative under any circumstances. That’s why even at the Solovki prison camp he stubbornly organized theatrical performances of Soviet hits: Lev Slavin’s The Intervention and Viktor Gusiev’s Slava.

Researchers spent many hours searching the NKVD archives looking for information on the famous artist’s exact place of death. We now know that Les Kurbas was executed, along with many other prisoners, in the Sandarmokh forest massif of Karelia in early November 1937, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the “Great October Revolution” – that’s how they used to call this event and how they celebrated its anniversary.

This huge ravine, hundreds of kilometers from Ukraine, is a gigantic grave where the crackling of human bones can be heard under the leaves. The doomed were lined up and shot, one by one. People, dead and alive, fell and rolled down into the ravine. Les Kurbas doesn’t have, and probably never will have, a personal burial place, as is customary in Christian tradition.

Re-Creation

There were many important events between the start and end of his earthly journey. Les Kurbas, who died at 50 after spending his last five years in repressive Soviet concentration camps, achieved more in his lifetime than countless others combined.

His exceptional creative nature was first manifested in his literary work. In 1906, with Ivan Franko’s blessing, Kurbas published his short story “In a Fever” in Literary-Scientific Bulletin under the pseudonym Zenon Myslevych. Written as a dialogue and full of youthful expression, this was his first literary attempt while in his penultimate year at the Ternopil gymnasium. Kurbas later began translating poems, plays, prose and theoretical works, writing plays and screenplays.

The next step in his creative path was acting, where his talent was evident immediately. Kurbas never studied acting as such and made his stage debut at the age of 22. His amateur and professional roles drew the attention of the Ukrainian, Polish, Jewish and German press. People couldn’t help but notice the handsome, slender, tanned young man with a Greek profile, normal facial features and a high forehead, who wore a bow instead of a tie and loved wide brim hats.

Kurbas’s acting potential reaches its peak during the terrible wartime years of 1917-1920. He performed classical Ukrainian drama at the Sadovskyi Theater in Galicia and created the tragic image of Oedipus Rex and comic image of Leon in Woe to the Liar! at the Young Theater. In 1919 he even tried his hand in dancing, having played the Shah in the ballet Arabian Nights at the Musical Drama Ukrainian Opera Theater. Kurbas’s last premiere role was Macbeth, which he performed for the first time in Ukrainian with the traveling Kyidramte.

Besides theater, Les Kurbas also worked in cinema. In 1924-1925 he directed Vendeta, McDonald and Arsenaltsi. However, most of his vast creative heritage was lost because it simply couldn’t be preserved: performance aren’t preserved for the future. We will never see Kurbas’s films, his notes, private documents, things. All that remains from the material are designs for costumes and sets, and from the spiritual – excerpts from his diary and numerous theoretical articles and essays on theater and art.

Having assumed the role of leader of aesthetic reforms, Les Kurbas constantly declared his position and promoted changes in artistic priorities. His texts were written under various circumstances. Some were born after the creation of new theater groups, changes in repertoire, cultural and political discussions. Over the course of fifteen years he published some twenty different appeals, open letters and major articles, and in most of them he outlined the artistic vectors he intended to follow with like-minded people, pointed to the unacceptable, the outdated, and the irrelevant.

Kurbas’s declarations can be divided into three groups, each of which point to changes in his aesthetic priorities and prevailing ideological attitudes. The first includes texts about the Young Theater in 1917-1919 that are marked by the greatest focus on acting techniques and general aesthetic and philosophical issues. The second are texts written during his time with Berezil, where the main focus is on new stage imagery and its impact on the human psyche, consciousness and subconscious.

The third group of manifestos relates to the Kharkiv period. Kurbas sees theater as a tool of cultural and social influence, touches on issues of stage genres, relevance and audience acceptance of plays. “Accentuated manifestation” and “accentuated influence” in theater become key during his participation in Soviet-inspired literary and artistic discussions in 1927-1929, after which Ukrainian artists were divided into “clean” and “not clean,” “loyal” and “not loyal.”

Even with the variety of issues and topics that Kurbas touched upon, nearly all his texts are marked by an absence of pragmatism and an ideological view on reality and nature of things. He understood creativity, and particularly theater, as being a manifestation of the human spirit. The human spirit is the driving force behind the creation of a work of art. This form of creative thinking, most likely embraced while studying at the University of Vienna, became instrumental throughout his life.

In his early manifesto “Theatrical Letter,” Kurbas published his secret hesitations about his chosen path in life. “Where should a bifurcated modern soul go?” he asks. The answer he gives himself is obscured, indirect, wrapped in a scroll of complex spiritual quests. The authors seems to waver between artistic incarnations: a schemer (bearer and embodiment of the ethical teachings of Ukrainian philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda) and a herald of sociopolitical ideas.

Life chose for him: Les Kurbas transformed from a dreamer and schemer into a public artist, a driver of cultural and social reform, a foreseer of his own victories and defeats.